Holocaust Speaker Tells His Story of Survival

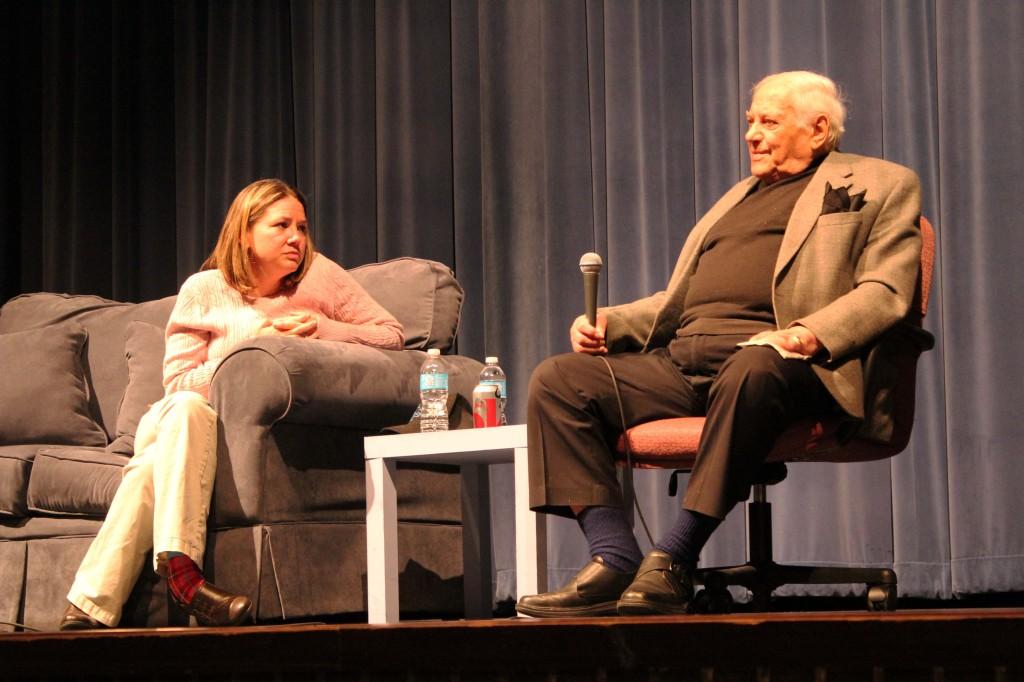

Struggling to climb up the stairs to the stage, the white-haired elderly man looks out at a sea of young faces all lit up by iPhone and iPad screens, none older than 17.

As survivor Jack Repp begins to speak, one by one the students put away their electronics and focus in on his heavily accented voice as he recalls that fateful day in 1939.

After all, he recounts the real-life story of a boy, only 15, not much younger than themselves.

“God bless you all, you don’t know how thankful and appreciative you ought to be to the United States of America,” Jack, who is now 90, said. “You live in the best country in the world.”

Since her class was learning about literature in relation to the World War II era, English teacher Cindy Malone invited Jack to come speak about his experience in the Holocaust last week in the PAC.

“We hear the speaker in an effort to understand how we in America were experiencing the war so differently (than) they did on the other side of the world,” she said. “But honestly, I just want everyone who can to hear a survivor before there are no more who can talk to students.”

The audience included mostly juniors who had also read “Night” by Elie Wiesel the year before.

“I have always looked for experiences to give students that are a little different or might capture their imagination and might make them want to read and learn,” Malone said. “I noticed that when I got students as juniors, the thing they liked the most from their sophomore year was reading Night. So I went with it.”

Jack, who spoke for almost two hours, began with his first experience involving the Nazi soldiers.

“During the school day they took all the teachers, threw them in the mud and beat them so you could imagine what was going to happen to you,” he said. “You were next in line.”

His time at school was replaced with physical labor.

“They took two volunteers; nobody volunteers but I looked a little bit more taller and more athletic than the kids so I volunteer,” Jack said. “They tied up my hands and hung me by my hands. Then hit me in the back until the blood came out. Then I was let down to work another 8 hours for a 12-hour day.”

As the days wore on, he was moved to the Kielce ghetto.

“We (Jews) were suppose to be God’s chosen people so I said Dear God how about you chose somebody else for a change,” he said.

Jack said that the penalty was death for those who were disrespectful to Nazi soldiers.

“Every German soldier could be the judge, could be the juror, could be the executioner,” he said.

Jack was relocated to the Dachau and then the Auschwitz Concentration Camps where an inscription on the entrance gate read, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” which translates to “work will set you free.”

“I no longer had a name,” he said. “I was now prisoner 828.”

For a few years, he worked in an ammunition factory making machine guns.

“Sixty-nine years after the war you can blindfold me today, and I can put one of them together,” Jack said.

The fact that he was imprisoned never left him.

“After six years of being incarcerated, I was jealous of the butterfly,” he said. “The butterfly was able to sit down and get away. I couldn’t go anywhere.”

The soldiers who came to liberate his camp provided a shower and clothes before telling him he was free.

“I was 21-years old, it was six years after the war (started),” Jack said. “I weighed 69 pounds, not a tooth in my mouth.”

He said he looked up to men like General Dwight D. Eisenhower, General George Patton and all the soldiers who were involved in his release.

“If you are in the military, you go out and you risk your life (to) save the life that is sitting down here now,” he said. “You save an entire planet, that’s what gods (do).”

After his liberation, he said he had a debt to repay.

“I was hunting Nazis and bringing them to the tribunal,” he said. “I was at every hanging and every killing. I touched every rope. This is what I did for four years without pay.”

He was offered asylum and given a Visa to come to America, where he had family in Greenville, Texas.

“After 90 days (here) I opened (my own) department store in Downtown Dallas,” Jack said.

After seeing racism in the south, he told students how he hired African-Americans to work for him because after being a slave himself, he refused to discriminate against anyone.

“The one thing that really stuck with me was that he sees all people as equal and that no person is any better than someone else because of the color of their skin,” junior Kenyatta Theriot said.

One reason he shares his story, he said, is so similar genocide situations in Uganda, Syria and Egypt are not forgotten.

“There has to be people like me,” Jack said. “Hitler took everything from me, but he didn’t take my mind.”

Theriot said that hearing a Holocaust survivor inspired him.

“With all the horrible things that happened, he was able to keep going and not just give up,” Theriot said.

As one of the Dallas Holocaust Museum founders, he has told his story to Malone’s students in previous years.

“He is very honest and that is refreshing,” Malone said. “He didn’t sugar coat things or say what he thought we wanted to hear.”

Jack said he wants students to understand how blessed they are to be in America and have freedom.

He said, “If you had been in the shape I was in, survive like I survived, do what I did, I think you would be grateful and thankful to God for every second, every minute, every hour you live on this planet.”